Music to listen to while reading:

Koreans have this ritual called doljabi — when a child turns one, they’re placed in front of various objects. Whatever object the child crawls towards represents a certain future or lifestyle: a pencil (intelligence), money (wealth), noodles (longevity), etc.

The tradition dates back to the early Joseon period; when child mortality in Korea was high, a first birthday was cherished by families across social classes and backgrounds. Of course, the idea that whatever object an infant crawls toward represents his/her future isn’t really subscribed to today, but it’s an interesting observation on how split-second choices can have a surprisingly major impact on one’s life.

Within the Bay Area Carnatic community, there’s a group of three brothers affectionately referred to as the “three gems” who each play the violin, mridangam, and flute. Jokingly, an aunty quipped that the brothers each crawled towards their instrument of choice when they were infants, and that set the path for their future in music.

It reminded me of an offhand comment from a family friend, who once remarked that he was a “mridangam guy in a violin body.” He’d been recruited into Carnatic violin because of his parents, but had little interest in the instrument and quit soon after. How might his life have been different if he’d enrolled in percussion lessons instead?

I’m fortunate enough that many of the choices my parents made for me ended up being ones that I myself would stand by. My parents decided, when I was a child, to enroll me in Carnatic music lessons. I happened to enjoy it, so I stuck with it. To my parents’ relief, I gave up on my pre-law aspirations to study something more practical (economics), and pursue a career in something more stable (finance). How much of that was truly my choice and how much of that was influenced by my family/the greater Mission community, I don’t really know, but I’m relatively content with the decision retrospectively.

Doljabi makes me think about a couple of things. How do we react when we’re presented with choices? How do we react when those choices are made for us? And, how do we react in the absence of choice?

Making the right choice

I’d classify myself as someone who’s relatively non-confrontational. So, when I’m faced with a bunch of options, I tend to freeze. When I was a kid, I’d get overly stressed at Indian restaurants, the myriad of dosa possibilities overwhelming me (onion chili rava masala vs. onion chili ghee dosa??).

Amused by my indecision, my mom would always tell me that there’s no wrong choice when it comes to dosa; they’re all good. While this might’ve been true for dosa, what scares me more are situations where there’s really no going back.

Choosing the right college, for example, is a decision you make when you’re 18, barely old enough to have tasted the real world and unaware of the risks that come along with it. In all honesty, I didn’t put too much thought into where I went for college. I didn’t really know what I wanted to study, so a liberal arts college felt like my best bet to do that. Fortunately, I’m happy with my decision — I’ve managed to find a major I’m interested in, friends I get along with, and clubs where I can explore my hobbies. I can’t help thinking, though, that I just happened to get lucky here. Choosing a college is one of those things that you can’t really go back on, yet also one of those things that sets up your future the most.

I went through so much of high school exempt from making “real” decisions. Before leaving home, no decision truly feels that permanent, as there’s always a legitimate fallback option. In college, though, things feel more tangible. Choosing a major means choosing a job, choosing a job means choosing a career path, and choosing a career path means choosing a future. No amount of five- or ten-year plans could erase the fear that this kind of decision-making brings.

At times, I’m almost grateful for Indian stereotypes. When doctor, banker, and engineer are the only acceptable career paths, it leaves little room for interpretation. I quickly realized after taking AP Biology that I wasn’t cut out to be a doctor, so I set out toward chemical engineering. When that didn’t pan out, finance was the only logical next step. Like so, I’ve successfully managed to avoid confrontation in that none of my life choices have actually been avant-garde enough to disrupt the status quo.

Decision-making under uncertainty

Another aspect of decision-making I’ve been thinking about recently is decision-making under uncertainty. I’m someone who likes to know my options, and it’s a terrifying thought to not know exactly what’s coming next in my life. Yet, uncertainty is the basis of nearly every financial market or social situation. You can’t always predict what a market or person will do, so you try your best to predict the outcome based on the limited information you have.

I was hanging out with a friend recently who started to explain some theories of market design to me (why this came up, I don’t exactly remember, but it was a welcome discussion). He posed the following scenario to me.

Imagine you have a bag filled with red and blue marbles. You don’t know how many of each are in the bag, but your objective is to figure out whether the majority of the marbles are red or blue. You and your friends take turns pulling a marble out of the bag. You get to see only the color of the marble that you draw, and based on that, you get to guess what color the majority of the marbles in the bag are. How do you think this situation would play out?

When the first player draws a marble (let’s say he draws a red one), he might guess that the majority of the marbles in the bag are red. He then places the marble back into the bag, shakes it, and hands it to the next player. That player again draws a red marble, and so announces to the group their suspicion that the bag is mostly red marbles. The third player then draws a marble. This time, it’s blue. But, since the last two players both drew red marbles, the third player decides to vote with the majority and guess that the majority of marbles in the bag are red. The fourth player now draws a marble. It’s blue, but since the last three players have all announced “red,” the fourth player also decides to guess red as well. It doesn’t take long until the entire system collapses, because no one’s sure what’s actually happening with the marbles.

This principle of “information cascade” is fairly common in social behavior and decision-making, when people tend to believe in the bandwagon effect even if convincing contrary evidence is placed before them.

There are a few assumptions that we make when thinking about the information cascade. One, humans are boundedly rational — we tend to make decisions rationally based on the information around us, but that information isn’t necessarily always complete or correct (ie., when the fourth player drew a blue ball, she didn’t know that the third player had also drawn blue but had guessed red because of the previous players). Alternatively, our knowledge of the world is limited, and there comes a point at which certain social pressures or impetuses prompt us to make suboptimal decisions.

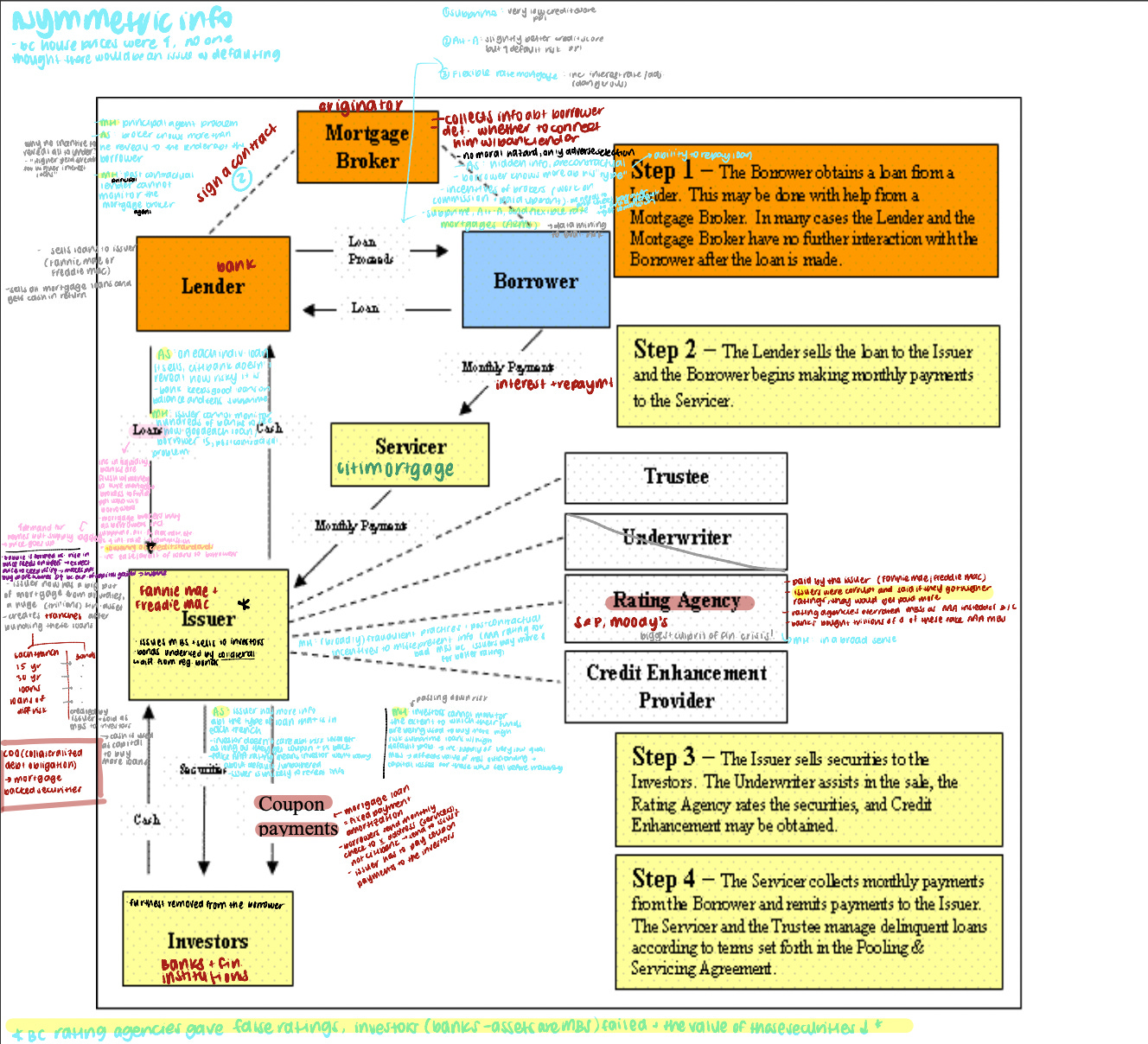

Several variant exercises prove something similar with regards to information asymmetry — like the lemons problem, for example, Akerlov’s theory that the quality of goods traded in a market can degrade in the presence of information asymmetry or adverse selection between buyer and seller. The 2008 financial crisis was a monumental failure because of asymmetric information at every level of the financial system1.

So, how do we fix this (or use this to our benefit)? When I asked this to the friend, he pointed to Uber’s surge pricing algorithm as an example of intentionally limiting consumers’ choices such that the business profits. Of course, this isn’t the most consumer-friendly example, and I can see how hearing about Uber’s profit-maximizing strategy isn’t the most riveting for the average American.

Another, more egalitarian example of decision-making under uncertainty is with the second-price auction. In a second-price auction, bidders submit offers without knowing what the other people in the auction have wagered, and the highest-price bidder ends up paying the price of the second-highest bid.

Presumably, the second-price auction encourages bidders to go as high as they can, whereas a first-price (traditional) auction encourages conservatism. In a second-price auction, bidders are more “truthful,” bidding their own evaluation of what they think the item is worth.

The optimal strategy is to bid what you think the item is worth, bᵢ = vᵢ.

You might think to bid a greater bᵢ such that bᵢ > vᵢ, but you’ll still end up paying the second-highest bid. And, if you bid bᵢ > vᵢ and someone else bids cᵢ < bᵢ < vᵢ, you’ll still end up paying more than vᵢ, resulting in negative utility.

On the flip side, if you bid bᵢ < vᵢ, you’re less likely to win, and you’re still not any more likely to pay less for vᵢ. All in all, you’re better off betting truthfully in a second-price auction.

Second-price auctions are commonly used today in e-commerce, like Google’s advertising model.

There are, of course, a couple of weaknesses with the Vickrey second-choice auction. Once we introduce irrationality, multiagent operators, and proxy bidders to the equation, it becomes much harder to say definitively that a second-choice auction is ideal. Yet, the idea remains interesting: there’s so much to decision-making that one has to consider in the absence of reliable data. Auction theory, and particularly non-cooperative games, are specifically fascinating to me, and maybe I’ll have more observations to share on them soon.

Extended rant on game theory aside, the point I was trying to make was that decision-making under uncertainty requires a certain level of overthinking, but that too much overthinking can place you back at square one. Perhaps this is a life lesson for someone like me, a chronic overthinker to the point of indecision.

Wrapping up

To bring things back to doljabi, I think the tradition is pretty harmless and honestly funny — I’ve heard of Gen Z Korean couples putting out things like video game controllers and golf balls for their babies. I don’t think there’s a huge implication on one’s future life prospects based on what arbitrary object they crawl towards as an infant.

There’s probably not too much harm in parents making certain life choices for their kids, either. After all, my parents enrolled me in bharatanatyam lessons the same time they put me in music classes, and I quit dance after barely a year. That too, parents’ decisions on these things are usually well-intentioned and often lead up to some sort of life lesson/teachable moment anyway.

When it comes to making my own decisions, I’m still riding on somewhat of a pre-determined “desi kid’s guide to success” blueprint. Making decisions under uncertainty is new to me, and I’m not yet at a point where I’d drop out of college and join a startup, or “follow my passions” and do something creative with my life, but maybe that’s something to work towards in the future.

Signing off for now, Tanisha.

Please see this diagram I made for my econ seminar last year — I put way too much effort into color-coordinating it just to never use it again.